Removal of reference to domestic sale, role of the purchase order, sales under customs warehouses and treatment of royalties/licence fees

The European Commission has published on September 17th 2020 an updated version of its customs valuation guidelines, related to the sale for export, within the meaning of Article 70 UCC and Articles 128 and 347 of the UCC Implementing Regulation, and the dutiability of royalties and license fees under Article 71 UCC and Article 136 of the UCC Implementing Regulation.

The first noticeable change in this guidance is the removal of any reference to the concept of domestic sale (a sale occurring between two EU companies can thus be considered as “the last sale for export”). Such change is consistent with the WTO Customs Valuation Agreement, as reminded by Advisory opinion 14.1 of the WCO Technical Committee on Customs Valuation.

This removal was made necessary since few EU administrations linked domestic sale and domestic movement of goods, meaning that they refused that a sale made between two EU entities served as basis for valuation purposes, even though that sale was accompanied by a cross-border movement of goods. This was causing two main practical issues:

- In cross trade operations (one physical flow between non-EU Seller A and importer C, with two financial flows between a non-EU Seller A to an EU buyer/reseller B and from an EU buyer/reseller B to EU importer C), importer C never holds the invoice of the sale between A and B. By requesting that invoice to be presented at customs clearance, customs administrations forced importers to declare on the basis of an alternative method. This was particularly problematic for transactions between independent parties, but also to some extent for transactions made between related parties.

- Customs duties were be paid on the price of the sale between A and B, while VAT was to be paid on the basis of sale between B and C. Reconciliation between the two sales for VAT purposes was a non needed complication.

By removing the concept of domestic sale, the Commission invites all member States to consider a sale made between two EU entities for customs valuation purposes.

In one significant clarification, the Commission stated that a purchase order (PO) cannot serve as the basis for determining the customs value of goods. Not only the transaction price can serve as basis for valuation purposes only when an offer (PO) is formally accepted by the seller, but the invoice should be available at clearance and presented as supporting document. The Commission seems to be willing to grant a central place to the invoice and this point of view regarding the exclusion of PO can be seen as consistent regarding the provisions of the International Vienna agreement on the international sale of goods.

Further important developments on the last sale for export concept were made regarding goods sold under customs warehouses. The Commission has provided some examples of various models involving successive sales of goods under warehouses, identifying which sale was to be seen as the last one for export. It seems that private sector was not properly consulted on these aspects, creating confusion and uncertainty for various models. Also, it appears that Member States are not fully aligned on certain points.

As a matter of illustration, examples 4a, 4b and 7 shown in the guidance describe a situation where an importer could find himself in a place where he is not in possession of the invoice of the sale for export identified by the Commission as the sale of reference and does not know (most of the time) that sale for export price. Transaction value will then not be available, and that importer would need to use an alternative method to clear the goods. But will any of them be relevant?

The comparative method (similar or identical good) will be useful, for example for those that import fungible goods, for which similar/identical goods imported can be easily found. Nevertheless comparison remain difficult for certain categories of goods. Deductive method is, when strictly applied, opened to goods sold in the EU in the condition as imported, and at the first commercial level after importation, to unrelated persons. Three cumulative conditions that render the use of this method very difficult, notably in warehouses were goods are usually (at least) minimally processed and sometimes declared for import following several successive sales. The computed value will be tough to apply in cases where an importer cannot access the invoice for the sale for export, it will not be able to access data on production costs. If those three methods are not relevant, only the fall back one, with all its uncertainty, will remain.

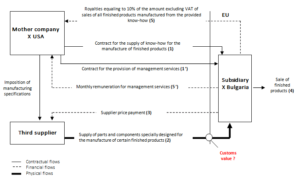

Last point, the guidance provides new examples of situations where royalties and license fees are dutiable. The definition of royalties and license fees was modified compared to the last version, and the following wording was removed: or the use of, or the right to use, industrial, commercial or scientific equipment. We witness an evolution leading to assess, in an increasing number of cases, the inclusion of intangible assets into customs value under article 71-1-b UCC (assists), rather than under article 71-1-c (royalties and licence fees). We have seen situations where the provision of intangible assets (know-how for example) compensated under the form of a license fee was included in the value as an engineering study in the sense of article 71-1-b-iv UCC. Sometimes even under 71-1-b-i UCC, as a material cost. In situations where intangible assets, provided in return of a payment of royalties, are identified as production factors, assessment of their dutiability will be made following article 71-1-b UCC rather than article 71-1-c, whose conditions make it more difficult for administrations to reintegrate in customs value. Case 3 (page 30 of the guidance) shows this new approach, which was underlined in Conclusion n°30 of the EU 2018 Customs Valuation Compendium.

Regarding Case 1, the outcome is in line with recent ECJ cases (GE Healthcare, Curtis Balkans), and with TCCV Commentary 25.1. The trend is, when assessing the payment as condition of the sale criterion, to give more weight to the actual manufacturing and supply organization than to the contractual provisions signed between the seller for export and the buyer.

***

The Customs and International Trade team of DS Avocats is at your disposal to provide you with any further information you may require.

CONTACT US :