Customs valuation, as a key tool in strategies to mitigate the impact of U.S. customs duties, has recently seen several developments that shed light on the treatment of prices subject to post-importation adjustments. In parallel, a growing and increasingly rich body of case law is progressively clarifying the framework within which customs authorities in the EU may legitimately resort to statistical databases as a method of value determination.

- Post-Importation Price Adjustments and Customs Valuation – Conflicting Perspectives

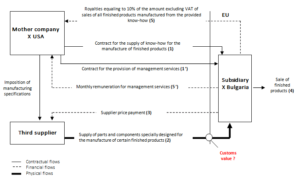

The matter of post-importation price adjustments underwent a turning point in 2016, when the CJEU ruled in the Hamamatsu case that a transfer price subject to post-importation adjustments—where the nature of the adjustment, whether upward or downward, could not be determined at the time of importation—was not acceptable for customs valuation purposes.

This ruling, unsatisfactory for both businesses and customs authorities, has led to increased confusion and a wide range of divergent practices across the EU. While a second case of this nature is currently under examination, the CJEU has just issued a new decision that seems to comfort the Hamamatsu case law.

On 15 May 2025, in Case C-782/23 – Tauritus, the Court ruled on the acceptability, for customs valuation purposes, of a provisional price subsequently adjustable based on the average market price and the exchange rate. Once these reference elements became known, corrective invoices were issued to establish the final price. In this case, the CJEU held that such a final price is acceptable under the transaction value method, provided the adjustment is based on objective, pre-established factors whose values are independent of the will of the parties — subject to amendment of the customs declaration.

However, the Court was careful to specify that the transaction value cannot be derived from an ex-post allocation of profits between the parties to the sale, based on a decision made by one of them. In a direct reference to the practice of post-importation transfer pricing adjustments, the Court reaffirmed its position and condemned the practice, as it had already done in Hamamatsu.

One can only regret such a restrictive approach, which is disadvantageous to economic operators, subject to increasing trade complexities, and at times creates complexity for customs authorities. Moreover, it is bound to oppose Case Study 14.4 of the Technical Committee on Customs Valuation (TCCV), adopted during the Committee’s 60th session and set to be formalized in late June 2025. This case study affirms, in principle, the acceptability of a price subject to post-importation adjustment for transaction value purposes. In this context, the year-end transfer pricing adjustment was documented, justified, and recorded in the accounts. On the basis of objective elements, it was therefore, deemed acceptable by the World Customs Organization (WCO) for determining customs value.

While TCCV instruments remain soft law, their adoption by consensus—meaning that all WCO members, including the EU, must agree — gives them significant weight with customs administrations. How will this instrument be received within the EU? It is difficult to predict. Nevertheless, this case study, which softens the rigid stance taken by the Court of Justice on the matter, is a welcome development for economic operators. Even if not fully embraced by the EU, the case study will remain a persuasive reference for all customs authorities, including those in countries whose regulations contain no provisions allowing for the treatment of transfer pricing adjustments for customs valuation purposes. And there are many such countries.

This may pave the way for greater facilitation for businesses in this area, in contrast to the increasing complexity arising from customs authorities’ growing reliance on statistical databases as a systematic method of valuation.

- Statistical Methods and Minimum Values: Inadequate Regulation of the Use of Statistical Databases

In the Keladis cases (Keladis I, C-72/24, and Keladis II, C-73/24), the Advocate General of the CJEU has recently delivered an opinion that speaks volumes about the intended use of statistical databases by customs authorities. For several years, the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) has been supplying national customs administrations with ‘acceptable minimum prices’ derived from EU customs data averages to flag ‘suspiciously low’ declared values. While these minimum prices may help identify potential undervaluation risks, they should not, in principle, be used to recalculate the customs value of goods and impose additional duties.

Otherwise, such a practice would amount to indirectly endorsing the use of predetermined minimum values, which is prohibited under the WTO Customs Valuation Agreement.

The opinion delivered by the Advocate General in this case (conclusions of 8 May 2025) provides welcome clarification regarding the conditions under which customs authorities may resort to statistical databases. It represents a (still too modest) step forward in reinforcing the procedural safeguards surrounding the use of such data — safeguards that have been weakened by recent CJEU rulings, notably Fawkes (C-187/21) and Commission v. United Kingdom (C-213/19), which left key questions unresolved concerning the use of statistical data for customs valuation purposes.

The Advocate General’s opinion first reaffirms that statistical databases can never serve as an autonomous basis for rejecting the transaction value. He emphasizes the strictly subsidiary nature of relying on aggregated data, which may only be used as a last resort. In this respect, will Keladis mark a turning point toward a more protective case law for economic operators, by clearly reaffirming the exceptional and non-normative character of using statistical databases?

The Advocate General also emphasized importers’ fundamental right to understand how their customs value was determined, to be able to defend themselves effectively. This is a crucial point — especially during audits — as it highlights the frustration frequently encountered by compliant operators subjected to statistical comparisons that lack convincing commercial or legal justification, and are accompanied by persistent demands for evidence to substantiate the reliability of their declared transaction values.

By doing so, the Advocate General has invited the Court to clarify the conditions under which customs authorities may rely on such databases to determine value, while reaffirming that transparency and individualized methodologies remain essential requirements of customs valuation. These conclusions therefore provide businesses with useful avenues to anticipate and protect themselves against reassessments based on statistical data.